THE

FIELDEN TRAIL

SECTION 3

Rake End via Gauxholme, Inchfield, Walsden and Bottomley

Now if you wish to continue or are starting Section 3, follow the road right from Dawson Weir towards Walsden. Just beyond Dobroyd Court, still on the right, you will pass some firemen's houses, with a beautifully carved Todmorden coat of arms over the front door. Opposite, on the other side of the road, is Waterside Mills, once the Fieldens' chief seat of manufacture, which will be discussed elsewhere. Beyond a mill gate and a clock on the right, Waterside House and the Laneside cottages appear on the left, opposite a council yard. This is the start of Section 3 of the Fielden Trail.

Laneside

Here, facing heaps of road grit in a council yard across the busy main road, stand the original cottages where Joshua Fielden (IV) set up his cotton business in 1782, after moving down here from Edge End. As a yeoman farmer, he had, with two or three handlooms at his disposal, combined farming with cloth manufacture at Edge End. Now, at Laneside he abandoned woollen manufacture and became a cotton spinner. The cottages you see here originally had two storeys. When Joshua Fielden moved here his family occupied one of the cottages, the other two being used for spinning. By this time he had been married nearly eleven years and had fathered two sons, Samuel and Joshua; and three daughters, Mary, Betty and Salley. (Mary Fielden of Dawson Weir was their niece ... Betty Fielden being the 'Aunt Lacy' referred to in Mary's letter).

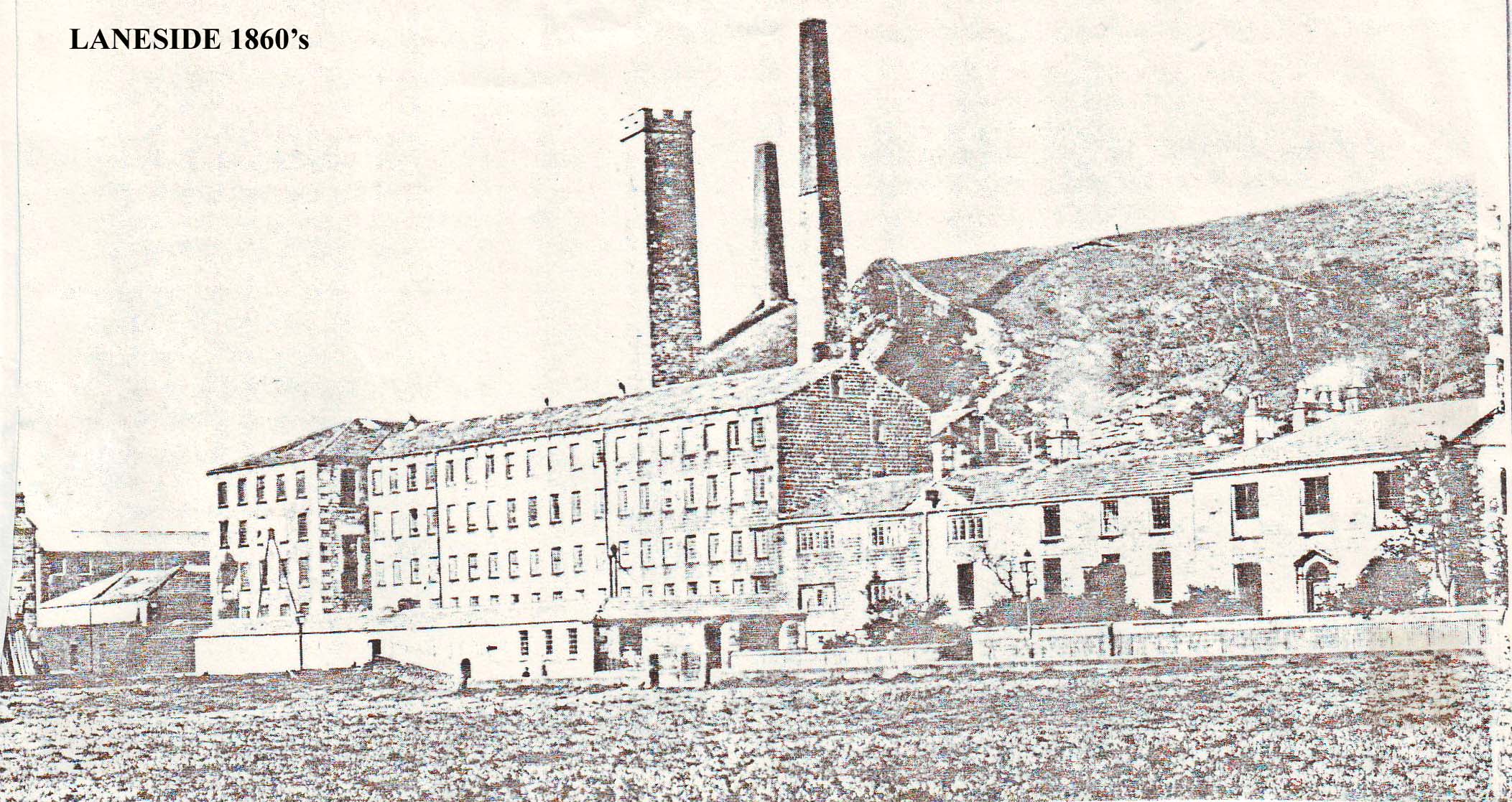

At Laneside the family prospered, mainly as a result of caution and hard work. They managed to keep consistently employed and gradually expanded their business as trade increased. A third storey was added, along with a warehouse crane (the walled up hole where it was mounted is still visible in the centre of the building). Later, when they decided to use steam power, they built a stone mill of five storeys and seven windows in length alongside one of the cottages (this is now demolished). The family home was also improved upon, the more grandly styled Waterside House being built onto the southern end of the cottages.

Four more children were born to the family at Laneside. Three sons, John, James and Thomas, and another daughter Ann (who died in infancy), raising the family total to nine. Here is the complete list with dates:

Samuel (1772-1822)

Mary (1774-1812)

Betty (1776-1836)

Joshua (1778-1847)

Salley (1780-1859)

John ('Honest John') (1784-1849)

Ann (1786-1786)

James (1788-1852)

Thomas (1790-1869)

Life at Laneside must have been rather more Spartan than that of succeeding generations. After all, there was a business to be established and a living to be made and, as was usually the case in the Lancashire cotton industry, you weren't spared the long hours and the hard work merely because you happened to be 't' maister's lad"!

John Fielden and his brothers were brought up "to the mill." From the age of 10 John worked 10 hours daily in the mill. Every Tuesday he would set off from Todmorden at 4am with his father to sell cloth in Manchester, returning around midnight with a cart full of raw cotton, having walked a distance of around 40 miles. It was a hard life and no doubt helped to form the attitudes and opinions that would be displayed by 'Honest John' in later life, when he was an M.P. fighting for the rights of his workers. His brothers also were to develop similarly radical opinions.

Why the sons of an old Tory like Joshua Fielden should grow up to become uncompromising radicals no doubt perplexed the pious old man. The boys appeared to Joshua to be "as arrant Jacobins as any in the kingdom." No doubt their education was a contributory factor. These were not the days when the sons of manufacturers were sent to private boarding schools for the wealthy; on the contrary, they were lucky to get an education at all. John and his brother were educated by a village schoolmaster who could neither read nor write but yet turned out pupils who were excellent readers and writers. This schoolmaster was well known for his Jacobin views: he supported the aims and ideals of the French Revolutionaries and instilled these ideas into his pupils. Not surprisingly, when political feeling was running high at the end of the 18th century, Joshua, the strong Tory, decided to remove his sons from the influence of "the holder of such revolutionary opinions". He obviously did so, but one suspects that perhaps it was rather like shutting the stable door after the horse had

bolted!

Joshua retired in 1803 though he lived on until 1811. The eldest brothers, Sam, Joshua and John took over management of the business, and changed the name of the firm to Fielden Brothers; while at some time after the death of Samuel in 1822, the premises became known as Waterside. Year by year the business expanded, first hand spinning, then water frames, then steam. In 1829 a large weaving shed

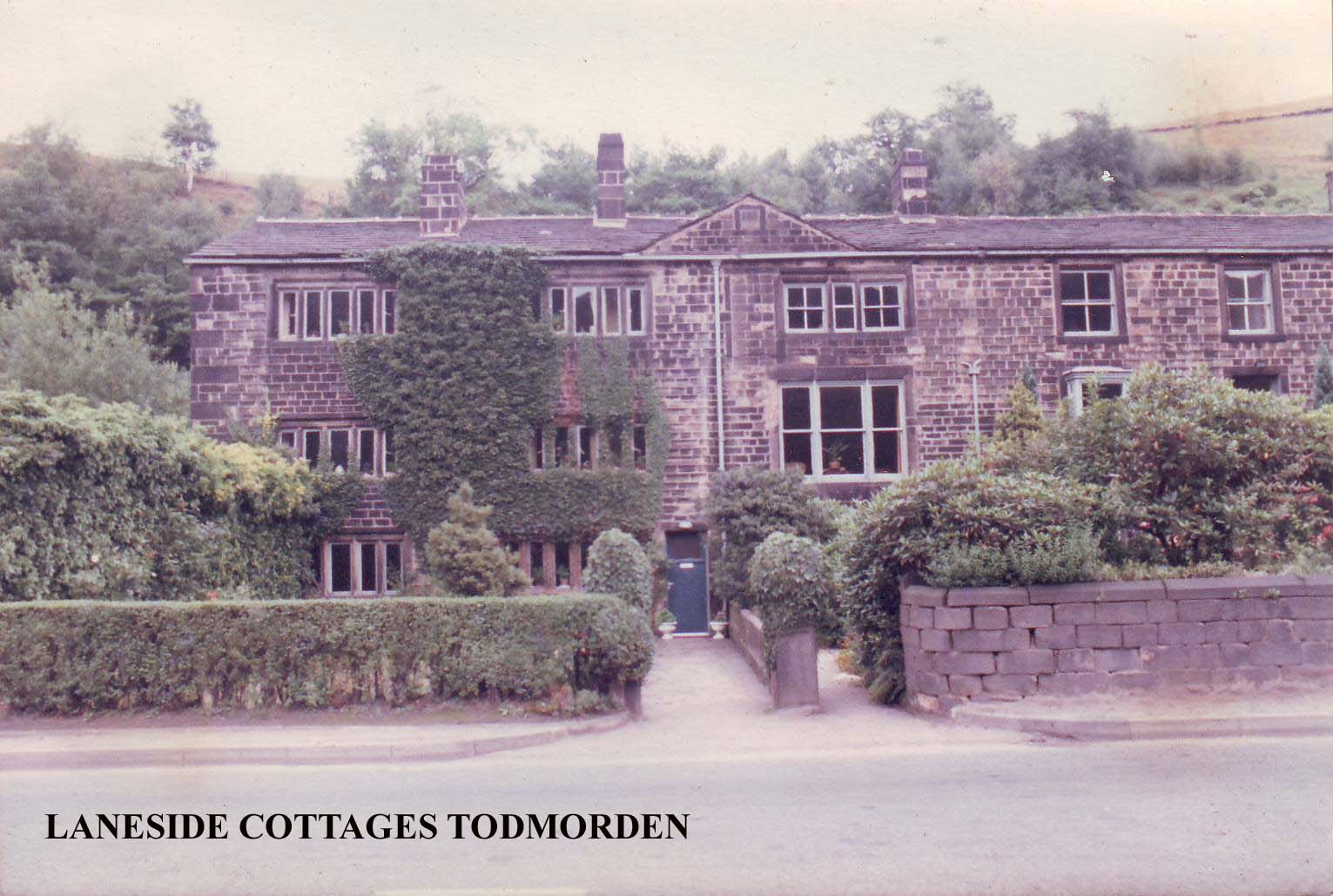

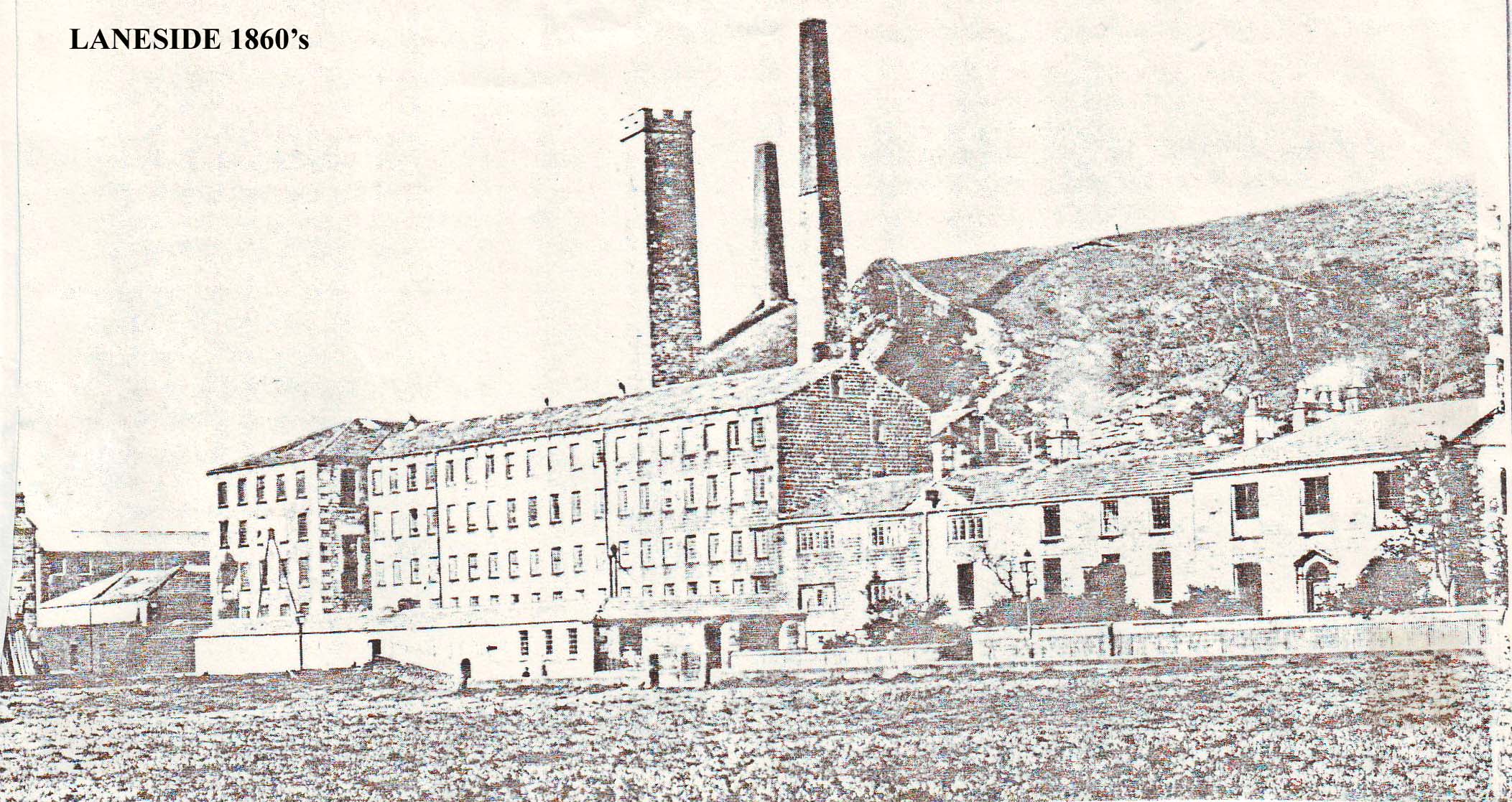

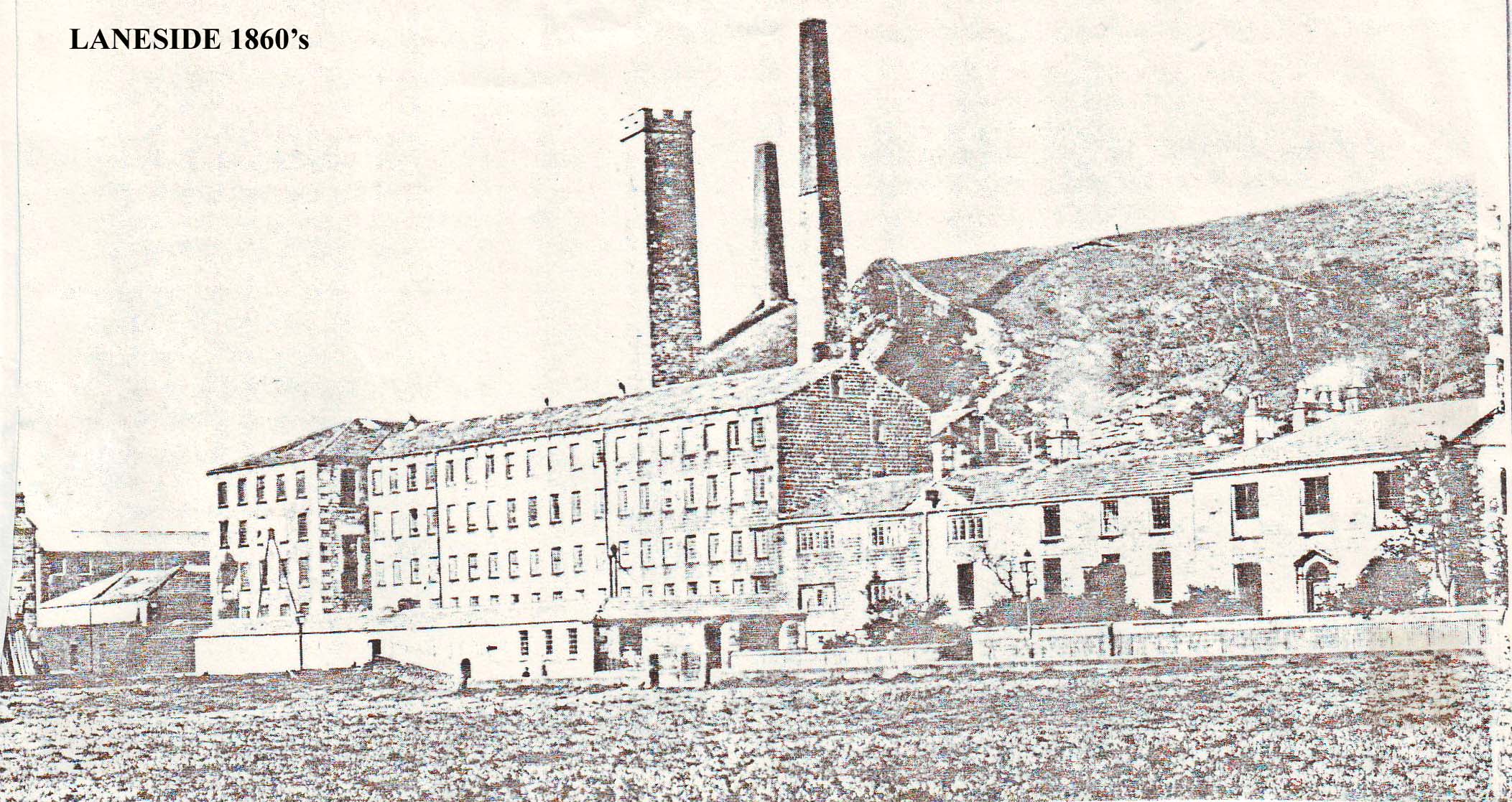

The cottages at Laneside, the birthplace of 'Honest John' Fielden. His father Joshua Fielden began cotton spinning in these cottages after moving from Edge End in 1782, and the little gable that carried the hoist for the cotton is clearly visible.

with a capacity for 800 looms was erected. At the time of its construction it was the biggest shed in the world. More spinning mills were built, and a second, even bigger weaving shed was erected. By 1844 the Fieldens had their own private railway siding and warehouses. Individual members of the family bought smaller mills from time to time, all used for spinning, in the valleys which ran up into the hills from the main valley. They owned mills as far afield as Mytholmroyd, and whole communities, Lumbutts for example, depended entirely on the Fieldens for their livelihood.

In the early days at Laneside the consumption of cotton was small, little more than a weekly cartload. But as transport improved so did the amount of cotton which could be processed in the Fielden's mills. In 1846 some 400 bales were used each week, each containing 500 lbs. In 1830 gasworks were constructed to light the mills, this being the first gasworks to be established by any private concern.

Even at the tender age of seventeen John Fielden began to show an interest in the welfare of his workers. In 1803 he and his brother Joshua opened a Sunday School in a large room where they taught reading, writing and arithmetic to the children who were employed in the factories during the week, and for whom there were no other chances for education. When in 1806 the town proposed forming a Sunday School Union for raising funds for the education of the children of the district's poor, John was one of the workers in the movement, and, for at least 12 years taught and superintended in the three voluntary schools of the Union, where 700 children were taught every Sunday, who (says the 1818 report) "were it not for the institution would remain in the grossest ignorance and spend the sabbath in a very unbecoming manner." The annual cost of educating these 700 schoolchildren was less than 60 pounds. Later Fielden was to run a school of his own for the town children, and this developed as a result of the birth of a new force in the religious affairs of the area: Unitarianism.

By 1817 Fielden Bros. employed 3000 handloom weavers. Wages did not exceed 10 shillings a week and when power looms came on the scene they fell as low as three and four shillings. Children at this time often learnt at home to weave, the warp and weft being brought to outlying farmsteads from spinning mills in the valley. Weavers with two ordinary looms received eight shillings a week; a loom with sheeting, 12 shillings. Loom Tacklers were much better paid, receiving 18 to 20 shillings a week. No doubt they enjoyed other privileges too ....a verse in the old song "Poverty Knock" runs:

"Tuner should tackle me loom

he'd rather sit on his bum

he's far too busy a Courtin' our

Lizzie an' ah cannot get him to coom . . ."

The days of the handloom weavers however, were numbered. Progressively the Fieldens moved away from manual methods in step with the rest of the expanding cotton industry, and turned to factories and power looms. Such a process could not be halted, it was inevitable. They had to keep up with the times. In 1829 Laneside and Waterside were merged, and, as we have already mentioned, a giant weaving shed was built. The Fieldens nevertheless actively aided the declining handloom weavers.

By the 1830's poverty and unemployment were widespread. The average weekly wage of the inhabitants in outlying districts in 1833 was 4s 3d, or 10s 3d per family. Corn was expensive, and oatmeal, skimmed milk and hard cheese formed the main diet of the working classes. For those without a job the predicament was even worse. The bad situation in the industrial north was by no means helped when in 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, which forced the unemployed to accept hard labour and imprisonment and humiliation in the workhouse. The Fieldens' active (and at one point violent) opposition to the new Poor Law forestalled the establishment of a Union Workhouse in Todmorden for many years, and forced the guardians to give outdoor relief.

After the Napoleonic Wars, fierce postwar competition had forced Fieldens to increase their working hours from 10 to 12 (11 on Saturdays). Horrific as this sounds, it was, nevertheless, fewer hours than those worked in most cotton mills at that time. To feel obliged to lengthen the hours of labour at a time when technological changes were making conditions more unpleasant shamed the radical mill masters and brought them out in support of factory reform. John Fielden was especially moved at the plight of the handloom weavers. In 1835 he wrote that he was "applied to by scores of handloom weavers who were so pressed down in their conditions as to be obliged to seek such work, and it gave me and my partners no small pain to be compelled to refuse work to the many that applied for it."

What was life like, then, in the new factories? In Todmorden, the Fieldens' mills and sheds stretched from Laneside to the heart of Todmorden, creating a solid block of industrial buildings that existed until very recently. Morrisons Supermarket today stands on their primary site. In 1835 they entered the merchant's house of Wildes

Pickersgill in Liverpool and eventually owned warehouse premises as well as properties in Manchester. Even though the Fieldens were the most enlightened of mill masters, actively concerned with the welfare of their operatives, conditions in mills were, nevertheless, harsh by modern standards. During the agitation for Factory Reform numerous books and pamphlets were published, some whitewashing the industry and describing conditions as ideal, others portraying cotton mills as "hell on earth". What were the facts?

One thing is certain: cotton mills were usually dirty, ill ventilated and filled with unguarded machinery. Dust was often a problem. The air was filled with minute particles of cotton called 'Fly'. The worst place for this was the 'Scutching Room' where bales of cotton were opened and prepared for the machines. In a Scutching Room the dust was often so dense that it enshrouded the workers like a fog. Temperatures could also be most uncomfortable. In a weaving shed it could get as hot as 92 deg. F. Ventilation varied from mill to mill, sometimes good, sometimes bad. Often it was the fault of the operatives themselves: underfed, badly clothed, they had a dread of cold air and would not open the windows. There were no safety regulations and moving parts were not screened or guarded. Driving belts with adjustable buckles were particularly dangerous. The shaft which delivered the power from the mill engine ran along under the ceiling and had drums on it at intervals, connected to the machines by drive belts. A careless mill girl could get her clothes (or worse still her hair) caught in the buckle on the moving belt and be flung over the driving shaft. There was no compensation for accidents, and families of victims had to rely on the charity of their workmates or the mill master.

Work was tedious and tiring. Mule spinning for example entailed walking endlessly to and fro. In 1832 John Fielden was elected first ever M.P. for Oldham. (This was a new seat created by the Reform Bill). One day, he and some fellow M.P.s met a deputation of working people in Manchester, one of whose delegates gave him a statement which contained a calculation of the number of miles which a child had to walk in a day in minding the spinning machine. It amounted to 25 miles! Adding the distance to and from home each day, the distance was often pushed up to 30 miles. 'Honest John' was naturally surprised at this revelation and wasted no time in investigating his own mills. To his dismay, he found that children there were walking nearly as far.

Last of all there were the hours. In his book The Curse of The Factory System, John Fielden laid the blame for all of the ills of the cotton industry at this single door. To reduce the monotony, to improve the health and safety of the workers, to prevent children from falling asleep at machines and walking these fantastic distances it was necessary to do one single thing, reduce the appalling hours of work.

However good the mills were, the hours were apt to vary enormously. Cotton was ruled by the trade cycle. If trade was bad there could be months of enforced idleness with short time and unemployment. When trade was good there was terrible overwork. It was by no means unknown to begin work at 6 am on Monday and work through till 11 at night on the following Tuesday. Then you would start at 6 am again on Wednesday and work through until 11pm on Thursday. Then you would finally start on Friday at 6 am and work until 8pm Saturday. Sunday was the Lord's Day. You got up early and went to worship. With these working times the total working week added up to around 120 hours. It is hardly surprising that accidents were so frequent with workers dozing off and falling into the machinery.

'Honest John' Fielden realised that such hours as these were not merely unjust, they were criminal... "a curse". Consequently he dedicated his life toward attaining a Ten Hours Bill, arguing, rightly as it turned out, that short time would not serve to reduce efficiency and output, but would actually increase it. In pursuit of this aim he was single minded and uncompromising. Yet John Fielden went further. Unlike many factory reformers, Fielden held Chartist principles and argued that the workers had a right not only to fairer working conditions, but also to an education and political emancipation. He was a true champion of the working man, and we will discuss his political career further along the Fielden Trail.

Back onto the Fielden Trail: from Laneside continue onwards along the road, towards Gauxholme, to reach Bar Street, where there is access to the canal towpath. Turn left here, passing a lock. Restoration work is in progress at time of writing, already the canal has been made navigable between Hebden Bridge and Todmorden, and work gangs are expanding outwards at both ends. It is sad that the canal was allowed to get into such a poor condition in the first place. Only now are we becoming aware of the immense amenity value of our inland waterways, but whether or not any 'real' jobs will emerge from this highly commendable restoration project yet remains to be seen. One can only hope that some lasting good will come out of it.

But back to the Fielden Trail. After passing Shade Lock the towpath runs under the railway beneath a superbly constructed skew bridge. The railway passes over here at a height of about 40 feet as it runs along the Gauxholme Viaduct. This section of railway, Hebden Bridge to Summit, was opened on 31st December 1840, the first passenger service along it being in March 1841. The Gauxholme Viaduct has 17 stone spans of 35 feet. This skew bridge over the canal has a 101 foot span with stone turrets at either end. It represents a considerable feat of engineering for its time. The girders are inscribed "R.J. Butler Stanningley Leeds 1840".

After passing Gauxholme Lowest Lock, immediately beneath the skew bridge, the towpath continues onwards towards Gauxholme. Pexwood Road can now be seen descending on the right, almost parallel with the canal. The next lock, Gauxholme Middle, is a place to reflect awhile before leaving the canal in favour of the neighbouring hills.

As might be expected, the story of the Fieldens is closely tied up with the arrival of both the canal and the railway. We have already seen how the Fieldens used the railway to their private advantage. Their enthusiasm for it, and the trading benefits it brought, had always been immense. It comes as a bit of a surprise therefore, to discover that when some 50 years earlier in 1790, a group of businessmen met in Hebden Bridge to propose a canal from Sowerby Bridge to Manchester, the Fieldens of Laneside were among the group of local mill owners who opposed the scheme!

The reason for this opposition was water. The canal promoters planned to divert streams feeding the river to supply the navigation, thus reducing the need to build numerous catchment reservoirs of their own. The Fieldens, along with most of the other Calderdale mill masters, insisted that they needed all of the available water for their mill goits in order to power machinery and to facilitate their bleaching, dyeing, fulling and printing processes. They complained that, in times of drought, mills would sustain considerable financial losses for want of water, and that the expanding industry, which was creating new mills in large numbers, was further stretching the already limited water resources. Water was all important to the mill masters, as it was often used again and again, falling from mills high up in the moors to newer mills in the valley bottoms. Indeed water was vital to their livelihood.

Because of this, when the Rochdale Canal Bill came before Parliament, it was thrown out on its second reading because of petitioning by mill owners and the proposals of a rival canal company which suggested a "less troublesome" route down the Ryburn Valley, which would have involved a tunnel under Blackstone Edge. In 1792 the Rochdale promoters held another meeting and resolved to try again. This time they set out to appease the mill owners, whose opposition they had previously underestimated.

It was suggested that only excess water should be fed into the canal, and under normal conditions streamways would flow under the canal, following their normal course. This time opposition softened slightly, so much so that a group of Todmorden mill owners were actually converted to supporting the canal. Among them were the Fieldens, who began to realise that the benefits of a canal might come to outweigh the disadvantages. The battle continued, but eventually, after agreeing to build catchment reservoirs on the moors, which would supply both mills and canals, the Rochdale promoters began to see light. Times were changing, steam engines were being installed in the mills, and it was apparent that the manufacturer's needs would soon be for coal rather than for water. On 4th April 1794 the Rochdale Canal Act was finally passed by Parliament.

Work began immediately, although the canal was not completed until 1802. The Act of Parliament for the Rochdale Canal gives a list of streams where only surplus water was available for the canal company. The streams were almost all in the Todmorden area, and many of them had Fielden properties along their courses... Mitgelden Clough, Warland Clough, Stoodley Clough and Lumbutts Stream. One entry reads:

"At the call or weir next above Todmorden belonging to Joshua Fielden", water might be turned into the canal "only when the stream shall flow over such call or weir more than 2 7/12 inches mean depth and 30 feet broad . . ."

By August 1798 the navigation was completed as far as Todmorden, and barges were bringing in coal and raw cotton. The canal company at the outset charged 2d per mile per ton of merchandise when a lock was passed, otherwise 11/2d per mile. Fielden Bros., one of the first companies to go over to steam power, profited immensely from the new navigation, yet water still continued to be a problem (especially after the Manchester section was opened) and it wasn't until 1827 that the canal finally had an adequate water supply (by which time we are on the eve of 'The Railway Age').

Nevertheless the Rochdale Canal played its part: barges brought in raw cotton and took away calicoes, fustians and velveteens. At this time 60,000 lbs of cotton were being spun weekly in Todmorden, and 7000 pieces of calico manufactured, so the Fielden's consumption of cotton had gone way beyond old Joshua's weekly horse and cart.

In 1825 a company was formed with the intention of building a Manchester to Leeds Railway, and in 1830 George Stephenson and

James Walker surveyed a route that would largely follow the line of the Rochdale Canal. The canal company, naturally enough, offered fierce resistance, but its days were numbered. Ironically the same 'progress' that had created the canal now brought about its demise.

Today the days of commercial carrying on the Rochdale Canal are long past, as MSC funded schemes struggle to develop it into an 'amenity waterway'. At present, the section of the canal that has been made navigable does not link up with the other navigable waterways and the Rochdale remains cut off from the rest of the northern canal network. We can only hope that all the ambitious plans of the restorers do not come to nought.

Continuing on our way, the towpath soon passes under the A681 Bacup Road, to arrive at Gauxholme Highest Lock, which has a massive set of new lock gates, the whole lock having been magnificently restored. Now it is time to leave the canal (for the moment at any rate), and to climb out of the valley. Turn right, passing over the lock footbridge. Opposite, a little further along the canal, is the Navigation Supply Co. which is housed in canalside buildings where there was once stabling for 14 boat horses and 14 cart horses, this being the old Gauxholme Wharf. Having crossed the bridge over the lock, bear right, passing through a gateway onto the Bacup Road. Opposite is the bottom of Pexwood Road which leads up the hillside to Dobroyd Castle and Stones. Not too long ago the hillside here was wooded, and somewhere near this road junction on Friday April 25th 1755 a crowd gathered at the bottom of Pexwood to hear the preaching of John Wesley. The relevant entry in Wesley's diary reads as follows:

"About ten I preached near Todmorden. The people stood row above row on the side of the mountain. They were rough enough in outward appearance, but their hearts were as melting wax. One can hardly conceive anything more delightful than the vale from which we rode from thence; the river ran through the green meadows on the right and the fruitful hills and woods rose on either hand . . ."

Shortly afterwards Wesley also preached and stayed at nearby General Wood, where he had a shirt repaired.

Here at Gauxholme, the Edge End Fieldens had a mill. From the will of Nicholas Fielden of Edge End, 1714:

"Item, I give and devise unto my said son Nicholas fourscore and ten pounds, together with all my right, title, benefit, etc.... and unto all that one drying killn, watercorn milln, and raising milln, commonley called Gauxholme Milln, and with the appurtenances, when he shall attaine ye age of twenty and four years . . . I witness whereof I, the said Nicholas ffeilden have hereunto put my hand and seal the ninth day of November 1714 . . .

Nicholas ffeilden of Edge End in Hundersfield in the County of Lancaster, Clothier."

Having entered the Bacup Road from the canal, turn left, and follow the route carefully to the gully behind Law Hey Farm, which is now derelict. Soon the left hand fence gives way to a low bank of earth and stone, more reminiscent of Cornwall, where such dikes take the place of stone walls, than Yorkshire. At the end of this bank we arrive at the ruins of Naze, a pile of rubble and dark stones in the midst of which stands an incongruous modern brick arched fireplace. Here are good views over to Stones.

From Naze the route leads without undue difficulty to Pasture Side. Just beyond Pasture Side turn left onto Rough Hey Lane, and follow it down the hillside to emerge on the edge of the valley overlooking Walsden, above woodland. Turn right, following the wall to Foul Clough Road opposite a three storeyed dwelling (Nicklety). This was once owned by Fieldens. Turn left, following the road steeply downhill to Inchfield Fold.

Inchfield

Inchfield has very long established associations with the Fieldens, although one would hardly realise this, looking at the present buildings. Here lived the Nicholas Fielden who we encountered in Section 1 courting Christobel Stansfield. Here also lived his son, Abraham, who married Elizabeth, the daughter and co heiress of James Fielden of Bottomley, thus uniting two branches of Fieldens.

By the early 17th century the Inchfield Fieldens were starting to proliferate and prosper. Abraham's brothers were firmly established at Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield. Now, stemming from this new marriage, succeeding generations of Fieldens were to become associated with Bottomley, which is the next stopping point on our

journey. Abraham was not the last Fielden to be associated with Inchfield. On the authority of the farmer's wife at Inchfield Fold I am informed that the three storeyed house at Nicklety belonged to one Thomas Fielden; and that the nearby mill, Inchfield Foundry, belonged to one Josiah Fielden, whose sister lived nearby at Inchfield House. Inchfield Fold Farm bears a datestone with the initials GTM 1631 and these, I am told, are the initials of George Travis, who built the house. What of the Fieldens? Well, according to 'Honest John's' family tree there are no 'Fieldens of Inchfield' mentioned after the early 17th century, so perhaps the land was sold off to George Travis, who built the present house.

From Inchfield Fold we simply follow the road into Walsden, emerging onto the busy A6033 road near the local branch library on the left. Cross the road to the Post Office opposite. Here is a chance to purchase refreshments if required.

Walsden is one of those place names with Celtic associations. Like Walshaw near Hebden Bridge it contains the place name element 'Walsh' or 'Welsh', the English term for 'foreigner', implying that there was a 'British' (ie Celtic) enclave in this area for many centuries after the English (and probably also Norman) conquests. Only the English could come along and call the native British 'foreigners' in their own country!

From Walsden Post Office continue onwards towards the church, and on reaching the canal bridge turn right onto the towpath, passing Travis Mill Lock on the left. From here onwards, until we reach Bottomley Bridge we simply follow the canal towpath again.

The Rochdale Canal on this section of the walk is now newly restored. It is a haunt for anglers and waterfowl, and the views to crags and steep hillsides are fascinating. The Rochdale Canal is soon joined by the railway on the right, which, just beyond Bottomley Bridge enters the Summit Tunnel, the first airshaft of which can be seen up on the hillside.

Before we set off for Bottomley let me give you some bits of information about this magnificent railway tunnel, which, when it was constructed, was regarded as being the wonder of its age. Work began on its construction in the spring of 1838, and on 5th September 1839 it claimed the lives of three men and two boys. On 22nd January 1840 three more workers were killed in the tunnel. By 31st March of that year the cost of the tunnel had exeeded the original estimate by 47,051 pounds. Finally, on 11th December 1840 the last brick was keyed in with a silver trowel. According to an account in the Manchester Guardian: "Gentlemen of the first respectability accompanied by numbers of ladies were seen with lighted candles advancing toward the place to witness the ceremony of the completion of the great work. The ladies and gentlemen present were invited to a cold collation at the Summit Inn, while the workmen were regaled within the tunnel". At the time of its completion the Summit Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel in the world, 2885 yards long and containing 23 million bricks.

At Bottomley Bridge we turn left, passing bungalows to ascend a superbly paved packhorse track which snakes up the hillside to Bottomley.

Bottomley

Bottomley is a key place in our Fielden saga. Generations of Quaker (and earlier) Fieldens lived and worked here, and at one time this small cluster of buildings was a small weaving settlement of some note, being situated on the Salter Rake Gate, the main packhorse route over to Lumbutts and Mankinholes, which was an eastern branch of the better known Reddyshore Scout Gate. (The word 'gate' in this context means 'way', and is an old Scandinavian word.) Cotton was spun in later times at nearby Waterstalls Mill. At Bottomley in 1561 lived James Fielden, son of another (unknown) Fielden who lived here in the reign of Edward VI. This James Fielden was great grandfather to the Elizabeth Fielden who married Abraham Fielden of Inchfield. The line runs as follows:

James Fielden Cisley

Jeffrie Fielden (lived at Bottomley in 1567)

James Fielden

Isabel (d. 1594)

Mary J. Clegg

Elizabeth (b 1594)

Abraham Fielden of Inchfield

Abraham and Elizabeth's sons, John and Joshua, as we have already mentioned became Quakers, and from them all the 'Bottomley Fieldens' are descended.

When I arrived at Bottomley whilst surveying the Fielden Trail, the weather was stifingly hot and the farmer there, Mr. Stansfield, invited us (the dog and I) in for a drink. Mr. Stansfield told me that as a boy he had farmed up at Kebs and Bridestones (this is, of course Stansfield ancestral territory). I thought it strange that just as Nicholas Fielden had inherited Stansfield lands by marriage way back in the 16th century, now, in the 20th century a Stansfield was in possession of lands that had traditionally belonged to the Fieldens since time immemorial! Strange indeed are the workings of fate.

Before we continue on our way, here is a little anecdote concerning the Fieldens of Bottomley:

"When Jane Fielden was a girl of nine years old, her grandfather, Samuel Fielden of Bottomley gave her a soup plate, which bears on the flat part a florid picture of Katharine of Aragon, stating that it belonged to her great grandmother and grandmother, who was then dead. 'It had always belonged to a Jane . . .' She kept it carefully until as an old widow woman living with her daughter at Strines Barn Walsden, she gave it to her grand daughter Jane Crowther, afterwards

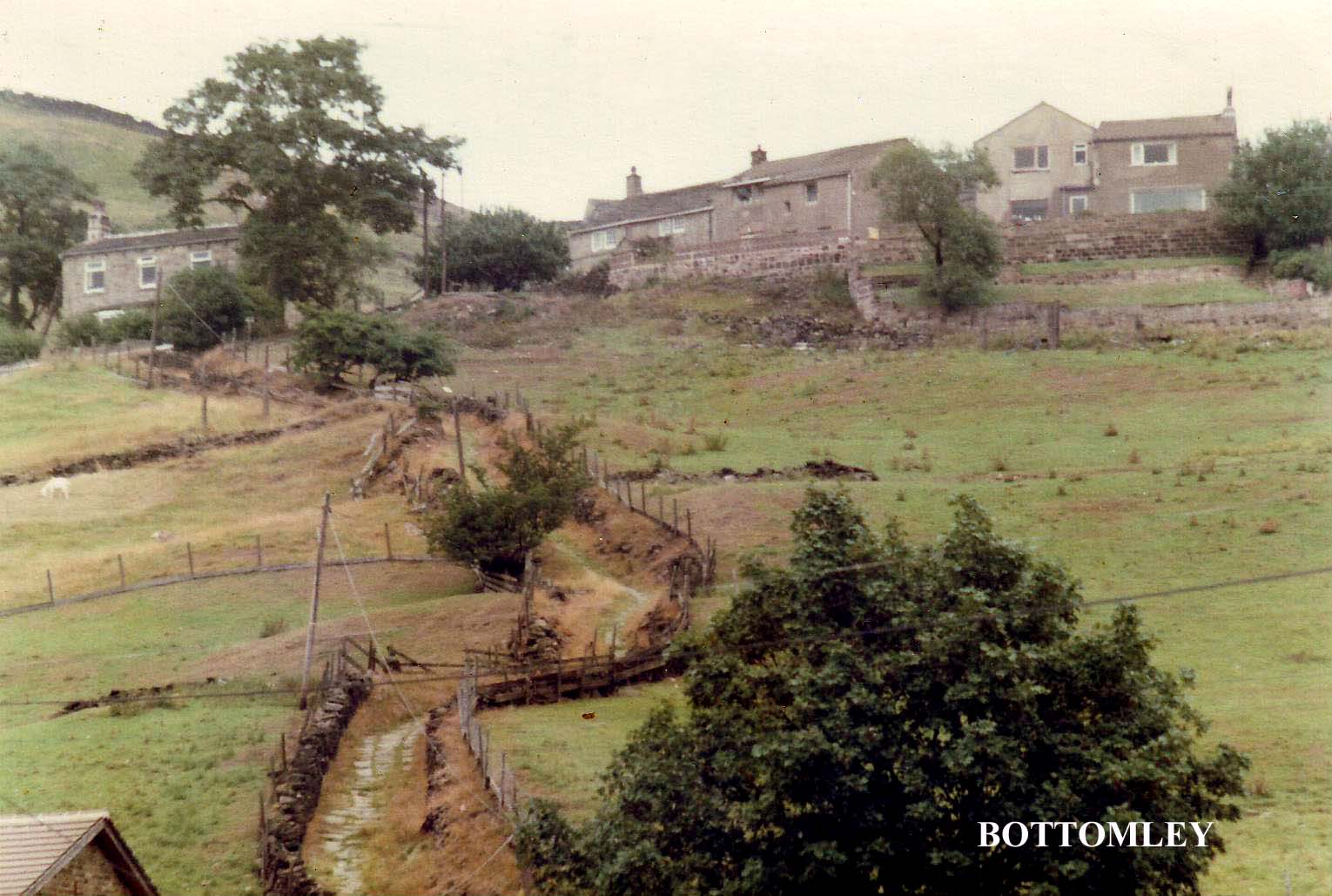

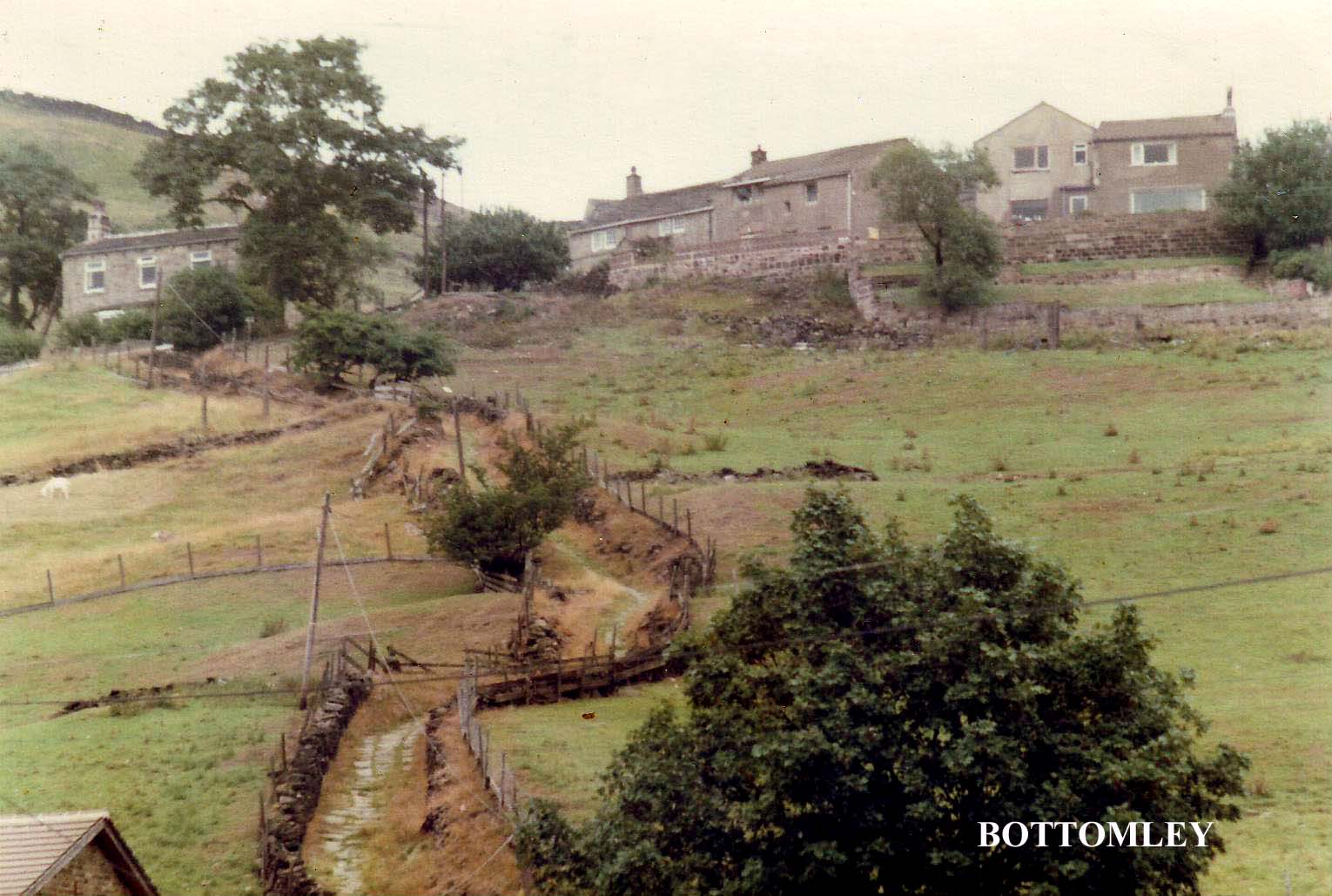

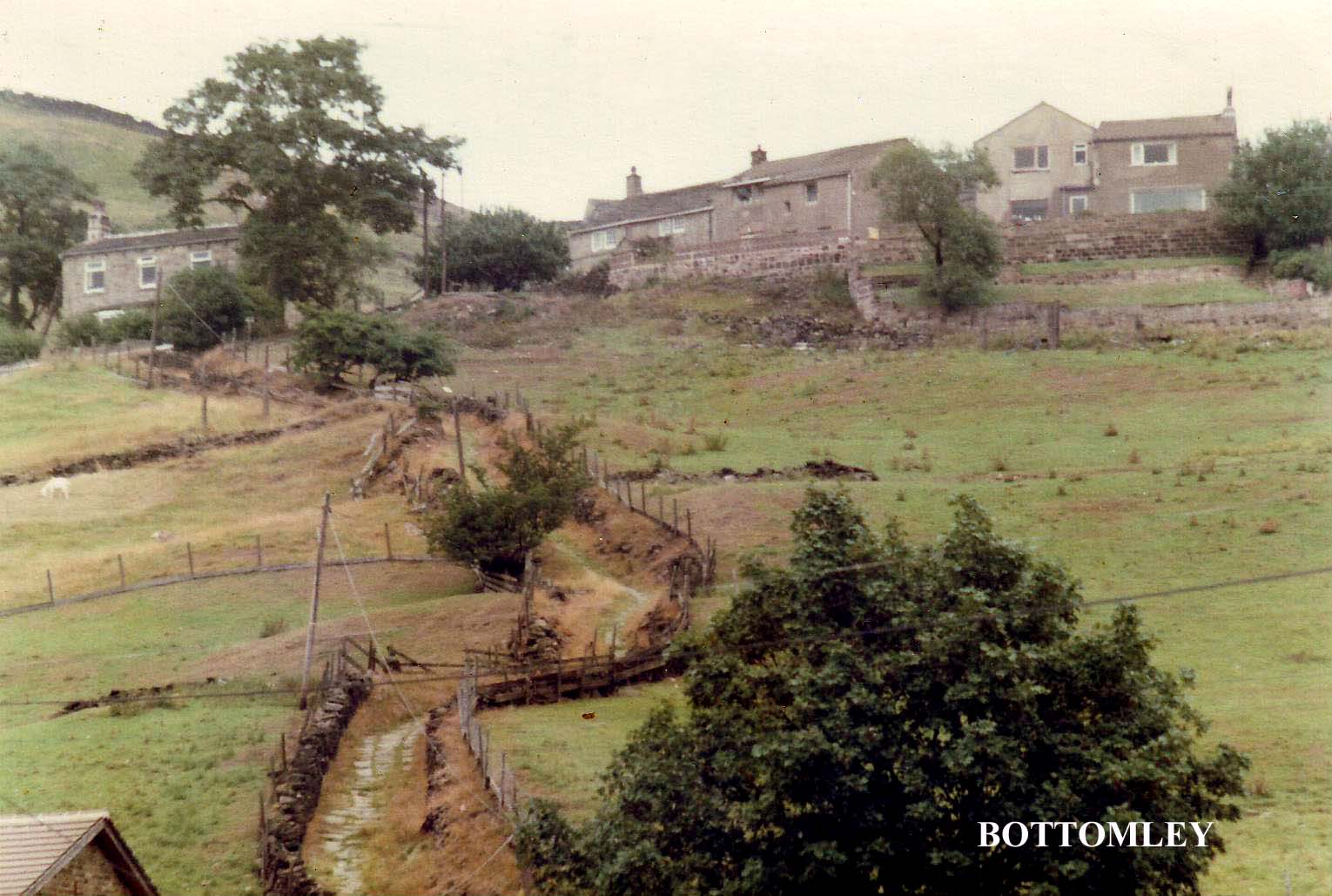

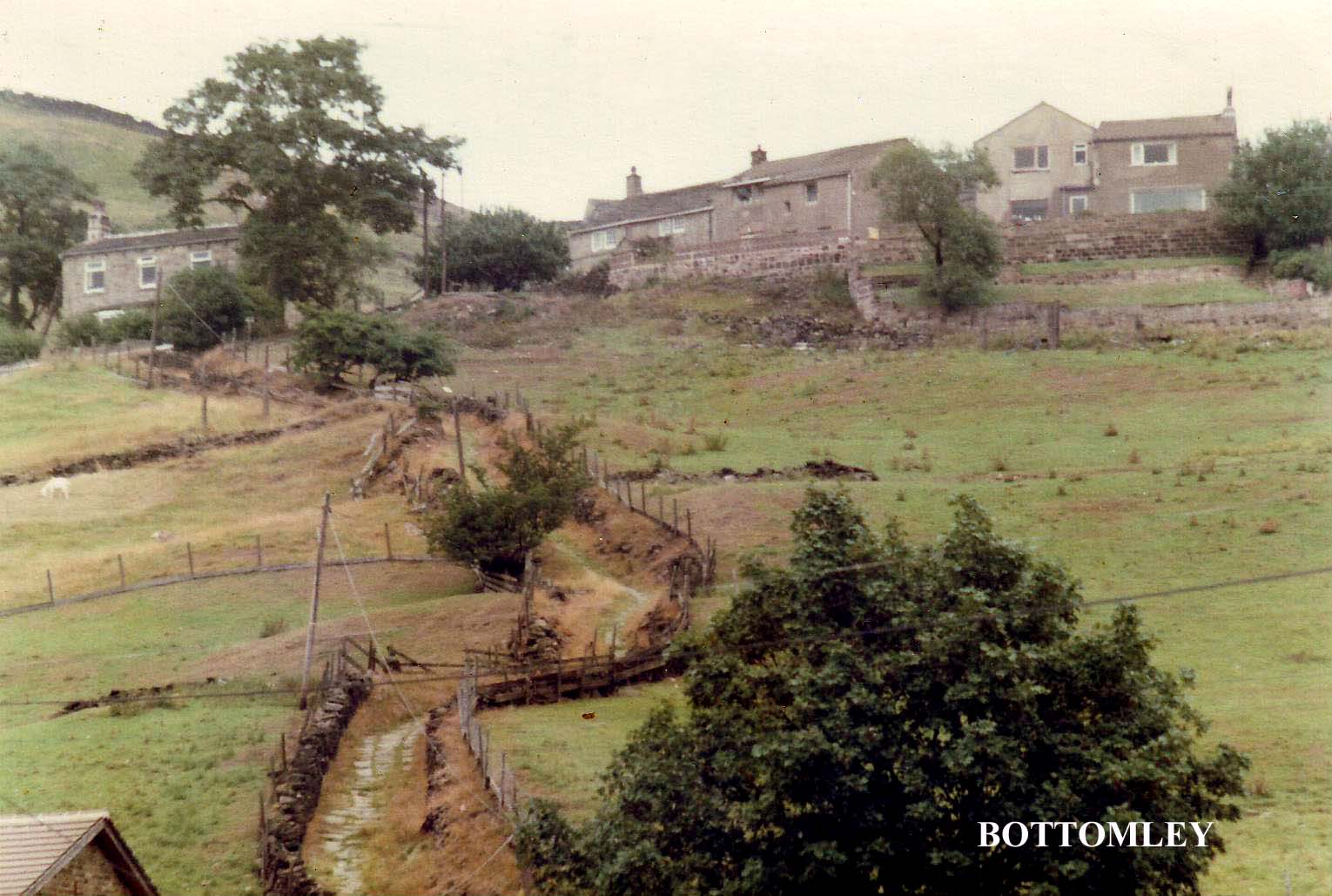

Bottomley, home of the Quaker Fieldens.

wife of John Travis, who gave it, (again) to her niece Jane (Crossley) Stenhouse, a few years before her death; so that the piece of old delfware is still travelling with the name 'Jane' .. .

From Bottomley the route crosses Bottomley Clough to emerge behind Deanroyd Farm. Then an old packhorse route, paved in parts, contours along the hillside to Hollingworth Gate, where we enter a metalled road leading to North Hollingworth.

Hollingworth too, has Fielden associations: Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden's son, Joshua (1) of Bottomley ('Honest John's' great great grandfather) married Martha Greenwood of Hollingworth before a J.P. on 21st October 1656. Their third son, Thomas, inherited Hollingworth, and he lived there until his death in 1762. There are three farmsteads here: Hollingworth Gate, South Hollingworth and North Hollingworth. As to which of these three houses was the residence of Thomas Fielden, is a question I am unable to answer. I would hazard a guess at South Hollingworth, but really the 'Fieldens of Hollingworth' demand more intensive research.

From Hollingworth Gate the tarmac road continues to North Hollingworth. Here, turn right, then left to a walled lane leading to a gate at the edge of open moorland. Beyond the gate is an extremely well preserved packhorse causey, which leads over moorland to Rake End. This is the Salter Rake Gate, an ancient route dating back to times unrecorded.

For my money this is one of the most interesting parts of the Fielden Trail. True, we have encountered old packhorse ways before, most notably at West Whirlaw, but in my view this is one of the most dramatic (and least chronicled) sections of packhorse track in the district. As its name suggests, salt was carried along this route from the salt pans (or 'Wiches') of Cheshire; yet all manner of goods and chattels, not to mention people, must have passed this way down through the centuries (until the Industrial Revolution that is!). Today, there is just the occasional rambler and the moorland wind and rain. What is most striking about this ancient moorland route is its sheer narrowness. If one packhorse train were to meet another coming from the opposite direction there is no way they would have been able to pass each other without one train or the other having to give way and take to the moor. No doubt the issue as to who should 'Give Way' created many a heated argument long ago, when these lonely moorland tracks were busy arteries of communication.

The old causey ascends the hillside to Rake End, where it meanders round the moor edge at the point where the Walsden Valley gives way to Calderdale. A faint path soon appears on the right, heading up the open moor towards the Basin Stone and Gaddings Reservoir. Here is the end of Section 3. For those wishing to get off the Fielden Trail at this point, simply follow the old packhorse way onwards to the Shepherd's Rest Inn on the Lumbutts Road. From here, turn left along the road, then after about a quarter of a mile, turn right down the farm road which eventually leads to Fielden Square in Todmorden (following the Calderdale Way), passing Shoebroad and picking up the latter part of Section 4 en route.

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

Now if you wish to continue or are starting Section 3, follow the road right from Dawson Weir towards Walsden. Just beyond Dobroyd Court, still on the right, you will pass some firemen's houses, with a beautifully carved Todmorden coat of arms over the front door. Opposite, on the other side of the road, is Waterside Mills, once the Fieldens' chief seat of manufacture, which will be discussed elsewhere. Beyond a mill gate and a clock on the right, Waterside House and the Laneside cottages appear on the left, opposite a council yard. This is the start of Section 3 of the Fielden Trail.

Laneside

Here, facing heaps of road grit in a council yard across the busy main road, stand the original cottages where Joshua Fielden (IV) set up his cotton business in 1782, after moving down here from Edge End. As a yeoman farmer, he had, with two or three handlooms at his disposal, combined farming with cloth manufacture at Edge End. Now, at Laneside he abandoned woollen manufacture and became a cotton spinner. The cottages you see here originally had two storeys. When Joshua Fielden moved here his family occupied one of the cottages, the other two being used for spinning. By this time he had been married nearly eleven years and had fathered two sons, Samuel and Joshua; and three daughters, Mary, Betty and Salley. (Mary Fielden of Dawson Weir was their niece ... Betty Fielden being the 'Aunt Lacy' referred to in Mary's letter).

At Laneside the family prospered, mainly as a result of caution and hard work. They managed to keep consistently employed and gradually expanded their business as trade increased. A third storey was added, along with a warehouse crane (the walled up hole where it was mounted is still visible in the centre of the building). Later, when they decided to use steam power, they built a stone mill of five storeys and seven windows in length alongside one of the cottages (this is now demolished). The family home was also improved upon, the more grandly styled Waterside House being built onto the southern end of the cottages.

Four more children were born to the family at Laneside. Three sons, John, James and Thomas, and another daughter Ann (who died in infancy), raising the family total to nine. Here is the complete list with dates:

Samuel (1772-1822)

Mary (1774-1812)

Betty (1776-1836)

Joshua (1778-1847)

Salley (1780-1859)

John ('Honest John') (1784-1849)

Ann (1786-1786)

James (1788-1852)

Thomas (1790-1869)

Life at Laneside must have been rather more Spartan than that of succeeding generations. After all, there was a business to be established and a living to be made and, as was usually the case in the Lancashire cotton industry, you weren't spared the long hours and the hard work merely because you happened to be 't' maister's lad"!

John Fielden and his brothers were brought up "to the mill." From the age of 10 John worked 10 hours daily in the mill. Every Tuesday he would set off from Todmorden at 4am with his father to sell cloth in Manchester, returning around midnight with a cart full of raw cotton, having walked a distance of around 40 miles. It was a hard life and no doubt helped to form the attitudes and opinions that would be displayed by 'Honest John' in later life, when he was an M.P. fighting for the rights of his workers. His brothers also were to develop similarly radical opinions.

Why the sons of an old Tory like Joshua Fielden should grow up to become uncompromising radicals no doubt perplexed the pious old man. The boys appeared to Joshua to be "as arrant Jacobins as any in the kingdom." No doubt their education was a contributory factor. These were not the days when the sons of manufacturers were sent to private boarding schools for the wealthy; on the contrary, they were lucky to get an education at all. John and his brother were educated by a village schoolmaster who could neither read nor write but yet turned out pupils who were excellent readers and writers. This schoolmaster was well known for his Jacobin views: he supported the aims and ideals of the French Revolutionaries and instilled these ideas into his pupils. Not surprisingly, when political feeling was running high at the end of the 18th century, Joshua, the strong Tory, decided to remove his sons from the influence of "the holder of such revolutionary opinions". He obviously did so, but one suspects that perhaps it was rather like shutting the stable door after the horse had

bolted!

Joshua retired in 1803 though he lived on until 1811. The eldest brothers, Sam, Joshua and John took over management of the business, and changed the name of the firm to Fielden Brothers; while at some time after the death of Samuel in 1822, the premises became known as Waterside. Year by year the business expanded, first hand spinning, then water frames, then steam. In 1829 a large weaving shed

The cottages at Laneside, the birthplace of 'Honest John' Fielden. His father Joshua Fielden began cotton spinning in these cottages after moving from Edge End in 1782, and the little gable that carried the hoist for the cotton is clearly visible.

with a capacity for 800 looms was erected. At the time of its construction it was the biggest shed in the world. More spinning mills were built, and a second, even bigger weaving shed was erected. By 1844 the Fieldens had their own private railway siding and warehouses. Individual members of the family bought smaller mills from time to time, all used for spinning, in the valleys which ran up into the hills from the main valley. They owned mills as far afield as Mytholmroyd, and whole communities, Lumbutts for example, depended entirely on the Fieldens for their livelihood.

In the early days at Laneside the consumption of cotton was small, little more than a weekly cartload. But as transport improved so did the amount of cotton which could be processed in the Fielden's mills. In 1846 some 400 bales were used each week, each containing 500 lbs. In 1830 gasworks were constructed to light the mills, this being the first gasworks to be established by any private concern.

Even at the tender age of seventeen John Fielden began to show an interest in the welfare of his workers. In 1803 he and his brother Joshua opened a Sunday School in a large room where they taught reading, writing and arithmetic to the children who were employed in the factories during the week, and for whom there were no other chances for education. When in 1806 the town proposed forming a Sunday School Union for raising funds for the education of the children of the district's poor, John was one of the workers in the movement, and, for at least 12 years taught and superintended in the three voluntary schools of the Union, where 700 children were taught every Sunday, who (says the 1818 report) "were it not for the institution would remain in the grossest ignorance and spend the sabbath in a very unbecoming manner." The annual cost of educating these 700 schoolchildren was less than 60 pounds. Later Fielden was to run a school of his own for the town children, and this developed as a result of the birth of a new force in the religious affairs of the area: Unitarianism.

By 1817 Fielden Bros. employed 3000 handloom weavers. Wages did not exceed 10 shillings a week and when power looms came on the scene they fell as low as three and four shillings. Children at this time often learnt at home to weave, the warp and weft being brought to outlying farmsteads from spinning mills in the valley. Weavers with two ordinary looms received eight shillings a week; a loom with sheeting, 12 shillings. Loom Tacklers were much better paid, receiving 18 to 20 shillings a week. No doubt they enjoyed other privileges too ....a verse in the old song "Poverty Knock" runs:

"Tuner should tackle me loom

he'd rather sit on his bum

he's far too busy a Courtin' our

Lizzie an' ah cannot get him to coom . . ."

The days of the handloom weavers however, were numbered. Progressively the Fieldens moved away from manual methods in step with the rest of the expanding cotton industry, and turned to factories and power looms. Such a process could not be halted, it was inevitable. They had to keep up with the times. In 1829 Laneside and Waterside were merged, and, as we have already mentioned, a giant weaving shed was built. The Fieldens nevertheless actively aided the declining handloom weavers.

By the 1830's poverty and unemployment were widespread. The average weekly wage of the inhabitants in outlying districts in 1833 was 4s 3d, or 10s 3d per family. Corn was expensive, and oatmeal, skimmed milk and hard cheese formed the main diet of the working classes. For those without a job the predicament was even worse. The bad situation in the industrial north was by no means helped when in 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, which forced the unemployed to accept hard labour and imprisonment and humiliation in the workhouse. The Fieldens' active (and at one point violent) opposition to the new Poor Law forestalled the establishment of a Union Workhouse in Todmorden for many years, and forced the guardians to give outdoor relief.

After the Napoleonic Wars, fierce postwar competition had forced Fieldens to increase their working hours from 10 to 12 (11 on Saturdays). Horrific as this sounds, it was, nevertheless, fewer hours than those worked in most cotton mills at that time. To feel obliged to lengthen the hours of labour at a time when technological changes were making conditions more unpleasant shamed the radical mill masters and brought them out in support of factory reform. John Fielden was especially moved at the plight of the handloom weavers. In 1835 he wrote that he was "applied to by scores of handloom weavers who were so pressed down in their conditions as to be obliged to seek such work, and it gave me and my partners no small pain to be compelled to refuse work to the many that applied for it."

What was life like, then, in the new factories? In Todmorden, the Fieldens' mills and sheds stretched from Laneside to the heart of Todmorden, creating a solid block of industrial buildings that existed until very recently. Morrisons Supermarket today stands on their primary site. In 1835 they entered the merchant's house of Wildes

Pickersgill in Liverpool and eventually owned warehouse premises as well as properties in Manchester. Even though the Fieldens were the most enlightened of mill masters, actively concerned with the welfare of their operatives, conditions in mills were, nevertheless, harsh by modern standards. During the agitation for Factory Reform numerous books and pamphlets were published, some whitewashing the industry and describing conditions as ideal, others portraying cotton mills as "hell on earth". What were the facts?

One thing is certain: cotton mills were usually dirty, ill ventilated and filled with unguarded machinery. Dust was often a problem. The air was filled with minute particles of cotton called 'Fly'. The worst place for this was the 'Scutching Room' where bales of cotton were opened and prepared for the machines. In a Scutching Room the dust was often so dense that it enshrouded the workers like a fog. Temperatures could also be most uncomfortable. In a weaving shed it could get as hot as 92 deg. F. Ventilation varied from mill to mill, sometimes good, sometimes bad. Often it was the fault of the operatives themselves: underfed, badly clothed, they had a dread of cold air and would not open the windows. There were no safety regulations and moving parts were not screened or guarded. Driving belts with adjustable buckles were particularly dangerous. The shaft which delivered the power from the mill engine ran along under the ceiling and had drums on it at intervals, connected to the machines by drive belts. A careless mill girl could get her clothes (or worse still her hair) caught in the buckle on the moving belt and be flung over the driving shaft. There was no compensation for accidents, and families of victims had to rely on the charity of their workmates or the mill master.

Work was tedious and tiring. Mule spinning for example entailed walking endlessly to and fro. In 1832 John Fielden was elected first ever M.P. for Oldham. (This was a new seat created by the Reform Bill). One day, he and some fellow M.P.s met a deputation of working people in Manchester, one of whose delegates gave him a statement which contained a calculation of the number of miles which a child had to walk in a day in minding the spinning machine. It amounted to 25 miles! Adding the distance to and from home each day, the distance was often pushed up to 30 miles. 'Honest John' was naturally surprised at this revelation and wasted no time in investigating his own mills. To his dismay, he found that children there were walking nearly as far.

Last of all there were the hours. In his book The Curse of The Factory System, John Fielden laid the blame for all of the ills of the cotton industry at this single door. To reduce the monotony, to improve the health and safety of the workers, to prevent children from falling asleep at machines and walking these fantastic distances it was necessary to do one single thing, reduce the appalling hours of work.

However good the mills were, the hours were apt to vary enormously. Cotton was ruled by the trade cycle. If trade was bad there could be months of enforced idleness with short time and unemployment. When trade was good there was terrible overwork. It was by no means unknown to begin work at 6 am on Monday and work through till 11 at night on the following Tuesday. Then you would start at 6 am again on Wednesday and work through until 11pm on Thursday. Then you would finally start on Friday at 6 am and work until 8pm Saturday. Sunday was the Lord's Day. You got up early and went to worship. With these working times the total working week added up to around 120 hours. It is hardly surprising that accidents were so frequent with workers dozing off and falling into the machinery.

'Honest John' Fielden realised that such hours as these were not merely unjust, they were criminal... "a curse". Consequently he dedicated his life toward attaining a Ten Hours Bill, arguing, rightly as it turned out, that short time would not serve to reduce efficiency and output, but would actually increase it. In pursuit of this aim he was single minded and uncompromising. Yet John Fielden went further. Unlike many factory reformers, Fielden held Chartist principles and argued that the workers had a right not only to fairer working conditions, but also to an education and political emancipation. He was a true champion of the working man, and we will discuss his political career further along the Fielden Trail.

Back onto the Fielden Trail: from Laneside continue onwards along the road, towards Gauxholme, to reach Bar Street, where there is access to the canal towpath. Turn left here, passing a lock. Restoration work is in progress at time of writing, already the canal has been made navigable between Hebden Bridge and Todmorden, and work gangs are expanding outwards at both ends. It is sad that the canal was allowed to get into such a poor condition in the first place. Only now are we becoming aware of the immense amenity value of our inland waterways, but whether or not any 'real' jobs will emerge from this highly commendable restoration project yet remains to be seen. One can only hope that some lasting good will come out of it.

But back to the Fielden Trail. After passing Shade Lock the towpath runs under the railway beneath a superbly constructed skew bridge. The railway passes over here at a height of about 40 feet as it runs along the Gauxholme Viaduct. This section of railway, Hebden Bridge to Summit, was opened on 31st December 1840, the first passenger service along it being in March 1841. The Gauxholme Viaduct has 17 stone spans of 35 feet. This skew bridge over the canal has a 101 foot span with stone turrets at either end. It represents a considerable feat of engineering for its time. The girders are inscribed "R.J. Butler Stanningley Leeds 1840".

After passing Gauxholme Lowest Lock, immediately beneath the skew bridge, the towpath continues onwards towards Gauxholme. Pexwood Road can now be seen descending on the right, almost parallel with the canal. The next lock, Gauxholme Middle, is a place to reflect awhile before leaving the canal in favour of the neighbouring hills.

As might be expected, the story of the Fieldens is closely tied up with the arrival of both the canal and the railway. We have already seen how the Fieldens used the railway to their private advantage. Their enthusiasm for it, and the trading benefits it brought, had always been immense. It comes as a bit of a surprise therefore, to discover that when some 50 years earlier in 1790, a group of businessmen met in Hebden Bridge to propose a canal from Sowerby Bridge to Manchester, the Fieldens of Laneside were among the group of local mill owners who opposed the scheme!

The reason for this opposition was water. The canal promoters planned to divert streams feeding the river to supply the navigation, thus reducing the need to build numerous catchment reservoirs of their own. The Fieldens, along with most of the other Calderdale mill masters, insisted that they needed all of the available water for their mill goits in order to power machinery and to facilitate their bleaching, dyeing, fulling and printing processes. They complained that, in times of drought, mills would sustain considerable financial losses for want of water, and that the expanding industry, which was creating new mills in large numbers, was further stretching the already limited water resources. Water was all important to the mill masters, as it was often used again and again, falling from mills high up in the moors to newer mills in the valley bottoms. Indeed water was vital to their livelihood.

Because of this, when the Rochdale Canal Bill came before Parliament, it was thrown out on its second reading because of petitioning by mill owners and the proposals of a rival canal company which suggested a "less troublesome" route down the Ryburn Valley, which would have involved a tunnel under Blackstone Edge. In 1792 the Rochdale promoters held another meeting and resolved to try again. This time they set out to appease the mill owners, whose opposition they had previously underestimated.

It was suggested that only excess water should be fed into the canal, and under normal conditions streamways would flow under the canal, following their normal course. This time opposition softened slightly, so much so that a group of Todmorden mill owners were actually converted to supporting the canal. Among them were the Fieldens, who began to realise that the benefits of a canal might come to outweigh the disadvantages. The battle continued, but eventually, after agreeing to build catchment reservoirs on the moors, which would supply both mills and canals, the Rochdale promoters began to see light. Times were changing, steam engines were being installed in the mills, and it was apparent that the manufacturer's needs would soon be for coal rather than for water. On 4th April 1794 the Rochdale Canal Act was finally passed by Parliament.

Work began immediately, although the canal was not completed until 1802. The Act of Parliament for the Rochdale Canal gives a list of streams where only surplus water was available for the canal company. The streams were almost all in the Todmorden area, and many of them had Fielden properties along their courses... Mitgelden Clough, Warland Clough, Stoodley Clough and Lumbutts Stream. One entry reads:

"At the call or weir next above Todmorden belonging to Joshua Fielden", water might be turned into the canal "only when the stream shall flow over such call or weir more than 2 7/12 inches mean depth and 30 feet broad . . ."

By August 1798 the navigation was completed as far as Todmorden, and barges were bringing in coal and raw cotton. The canal company at the outset charged 2d per mile per ton of merchandise when a lock was passed, otherwise 11/2d per mile. Fielden Bros., one of the first companies to go over to steam power, profited immensely from the new navigation, yet water still continued to be a problem (especially after the Manchester section was opened) and it wasn't until 1827 that the canal finally had an adequate water supply (by which time we are on the eve of 'The Railway Age').

Nevertheless the Rochdale Canal played its part: barges brought in raw cotton and took away calicoes, fustians and velveteens. At this time 60,000 lbs of cotton were being spun weekly in Todmorden, and 7000 pieces of calico manufactured, so the Fielden's consumption of cotton had gone way beyond old Joshua's weekly horse and cart.

In 1825 a company was formed with the intention of building a Manchester to Leeds Railway, and in 1830 George Stephenson and

James Walker surveyed a route that would largely follow the line of the Rochdale Canal. The canal company, naturally enough, offered fierce resistance, but its days were numbered. Ironically the same 'progress' that had created the canal now brought about its demise.

Today the days of commercial carrying on the Rochdale Canal are long past, as MSC funded schemes struggle to develop it into an 'amenity waterway'. At present, the section of the canal that has been made navigable does not link up with the other navigable waterways and the Rochdale remains cut off from the rest of the northern canal network. We can only hope that all the ambitious plans of the restorers do not come to nought.

Continuing on our way, the towpath soon passes under the A681 Bacup Road, to arrive at Gauxholme Highest Lock, which has a massive set of new lock gates, the whole lock having been magnificently restored. Now it is time to leave the canal (for the moment at any rate), and to climb out of the valley. Turn right, passing over the lock footbridge. Opposite, a little further along the canal, is the Navigation Supply Co. which is housed in canalside buildings where there was once stabling for 14 boat horses and 14 cart horses, this being the old Gauxholme Wharf. Having crossed the bridge over the lock, bear right, passing through a gateway onto the Bacup Road. Opposite is the bottom of Pexwood Road which leads up the hillside to Dobroyd Castle and Stones. Not too long ago the hillside here was wooded, and somewhere near this road junction on Friday April 25th 1755 a crowd gathered at the bottom of Pexwood to hear the preaching of John Wesley. The relevant entry in Wesley's diary reads as follows:

"About ten I preached near Todmorden. The people stood row above row on the side of the mountain. They were rough enough in outward appearance, but their hearts were as melting wax. One can hardly conceive anything more delightful than the vale from which we rode from thence; the river ran through the green meadows on the right and the fruitful hills and woods rose on either hand . . ."

Shortly afterwards Wesley also preached and stayed at nearby General Wood, where he had a shirt repaired.

Here at Gauxholme, the Edge End Fieldens had a mill. From the will of Nicholas Fielden of Edge End, 1714:

"Item, I give and devise unto my said son Nicholas fourscore and ten pounds, together with all my right, title, benefit, etc.... and unto all that one drying killn, watercorn milln, and raising milln, commonley called Gauxholme Milln, and with the appurtenances, when he shall attaine ye age of twenty and four years . . . I witness whereof I, the said Nicholas ffeilden have hereunto put my hand and seal the ninth day of November 1714 . . .

Nicholas ffeilden of Edge End in Hundersfield in the County of Lancaster, Clothier."

Having entered the Bacup Road from the canal, turn left, and follow the route carefully to the gully behind Law Hey Farm, which is now derelict. Soon the left hand fence gives way to a low bank of earth and stone, more reminiscent of Cornwall, where such dikes take the place of stone walls, than Yorkshire. At the end of this bank we arrive at the ruins of Naze, a pile of rubble and dark stones in the midst of which stands an incongruous modern brick arched fireplace. Here are good views over to Stones.

From Naze the route leads without undue difficulty to Pasture Side. Just beyond Pasture Side turn left onto Rough Hey Lane, and follow it down the hillside to emerge on the edge of the valley overlooking Walsden, above woodland. Turn right, following the wall to Foul Clough Road opposite a three storeyed dwelling (Nicklety). This was once owned by Fieldens. Turn left, following the road steeply downhill to Inchfield Fold.

Inchfield

Inchfield has very long established associations with the Fieldens, although one would hardly realise this, looking at the present buildings. Here lived the Nicholas Fielden who we encountered in Section 1 courting Christobel Stansfield. Here also lived his son, Abraham, who married Elizabeth, the daughter and co heiress of James Fielden of Bottomley, thus uniting two branches of Fieldens.

By the early 17th century the Inchfield Fieldens were starting to proliferate and prosper. Abraham's brothers were firmly established at Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield. Now, stemming from this new marriage, succeeding generations of Fieldens were to become associated with Bottomley, which is the next stopping point on our

journey. Abraham was not the last Fielden to be associated with Inchfield. On the authority of the farmer's wife at Inchfield Fold I am informed that the three storeyed house at Nicklety belonged to one Thomas Fielden; and that the nearby mill, Inchfield Foundry, belonged to one Josiah Fielden, whose sister lived nearby at Inchfield House. Inchfield Fold Farm bears a datestone with the initials GTM 1631 and these, I am told, are the initials of George Travis, who built the house. What of the Fieldens? Well, according to 'Honest John's' family tree there are no 'Fieldens of Inchfield' mentioned after the early 17th century, so perhaps the land was sold off to George Travis, who built the present house.

From Inchfield Fold we simply follow the road into Walsden, emerging onto the busy A6033 road near the local branch library on the left. Cross the road to the Post Office opposite. Here is a chance to purchase refreshments if required.

Walsden is one of those place names with Celtic associations. Like Walshaw near Hebden Bridge it contains the place name element 'Walsh' or 'Welsh', the English term for 'foreigner', implying that there was a 'British' (ie Celtic) enclave in this area for many centuries after the English (and probably also Norman) conquests. Only the English could come along and call the native British 'foreigners' in their own country!

From Walsden Post Office continue onwards towards the church, and on reaching the canal bridge turn right onto the towpath, passing Travis Mill Lock on the left. From here onwards, until we reach Bottomley Bridge we simply follow the canal towpath again.

The Rochdale Canal on this section of the walk is now newly restored. It is a haunt for anglers and waterfowl, and the views to crags and steep hillsides are fascinating. The Rochdale Canal is soon joined by the railway on the right, which, just beyond Bottomley Bridge enters the Summit Tunnel, the first airshaft of which can be seen up on the hillside.

Before we set off for Bottomley let me give you some bits of information about this magnificent railway tunnel, which, when it was constructed, was regarded as being the wonder of its age. Work began on its construction in the spring of 1838, and on 5th September 1839 it claimed the lives of three men and two boys. On 22nd January 1840 three more workers were killed in the tunnel. By 31st March of that year the cost of the tunnel had exeeded the original estimate by 47,051 pounds. Finally, on 11th December 1840 the last brick was keyed in with a silver trowel. According to an account in the Manchester Guardian: "Gentlemen of the first respectability accompanied by numbers of ladies were seen with lighted candles advancing toward the place to witness the ceremony of the completion of the great work. The ladies and gentlemen present were invited to a cold collation at the Summit Inn, while the workmen were regaled within the tunnel". At the time of its completion the Summit Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel in the world, 2885 yards long and containing 23 million bricks.

At Bottomley Bridge we turn left, passing bungalows to ascend a superbly paved packhorse track which snakes up the hillside to Bottomley.

Bottomley

Bottomley is a key place in our Fielden saga. Generations of Quaker (and earlier) Fieldens lived and worked here, and at one time this small cluster of buildings was a small weaving settlement of some note, being situated on the Salter Rake Gate, the main packhorse route over to Lumbutts and Mankinholes, which was an eastern branch of the better known Reddyshore Scout Gate. (The word 'gate' in this context means 'way', and is an old Scandinavian word.) Cotton was spun in later times at nearby Waterstalls Mill. At Bottomley in 1561 lived James Fielden, son of another (unknown) Fielden who lived here in the reign of Edward VI. This James Fielden was great grandfather to the Elizabeth Fielden who married Abraham Fielden of Inchfield. The line runs as follows:

James Fielden Cisley

Jeffrie Fielden (lived at Bottomley in 1567)

James Fielden

Isabel (d. 1594)

Mary J. Clegg

Elizabeth (b 1594)

Abraham Fielden of Inchfield

Abraham and Elizabeth's sons, John and Joshua, as we have already mentioned became Quakers, and from them all the 'Bottomley Fieldens' are descended.

When I arrived at Bottomley whilst surveying the Fielden Trail, the weather was stifingly hot and the farmer there, Mr. Stansfield, invited us (the dog and I) in for a drink. Mr. Stansfield told me that as a boy he had farmed up at Kebs and Bridestones (this is, of course Stansfield ancestral territory). I thought it strange that just as Nicholas Fielden had inherited Stansfield lands by marriage way back in the 16th century, now, in the 20th century a Stansfield was in possession of lands that had traditionally belonged to the Fieldens since time immemorial! Strange indeed are the workings of fate.

Before we continue on our way, here is a little anecdote concerning the Fieldens of Bottomley:

"When Jane Fielden was a girl of nine years old, her grandfather, Samuel Fielden of Bottomley gave her a soup plate, which bears on the flat part a florid picture of Katharine of Aragon, stating that it belonged to her great grandmother and grandmother, who was then dead. 'It had always belonged to a Jane . . .' She kept it carefully until as an old widow woman living with her daughter at Strines Barn Walsden, she gave it to her grand daughter Jane Crowther, afterwards

Bottomley, home of the Quaker Fieldens.

wife of John Travis, who gave it, (again) to her niece Jane (Crossley) Stenhouse, a few years before her death; so that the piece of old delfware is still travelling with the name 'Jane' .. .

From Bottomley the route crosses Bottomley Clough to emerge behind Deanroyd Farm. Then an old packhorse route, paved in parts, contours along the hillside to Hollingworth Gate, where we enter a metalled road leading to North Hollingworth.

Hollingworth too, has Fielden associations: Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden's son, Joshua (1) of Bottomley ('Honest John's' great great grandfather) married Martha Greenwood of Hollingworth before a J.P. on 21st October 1656. Their third son, Thomas, inherited Hollingworth, and he lived there until his death in 1762. There are three farmsteads here: Hollingworth Gate, South Hollingworth and North Hollingworth. As to which of these three houses was the residence of Thomas Fielden, is a question I am unable to answer. I would hazard a guess at South Hollingworth, but really the 'Fieldens of Hollingworth' demand more intensive research.

From Hollingworth Gate the tarmac road continues to North Hollingworth. Here, turn right, then left to a walled lane leading to a gate at the edge of open moorland. Beyond the gate is an extremely well preserved packhorse causey, which leads over moorland to Rake End. This is the Salter Rake Gate, an ancient route dating back to times unrecorded.

For my money this is one of the most interesting parts of the Fielden Trail. True, we have encountered old packhorse ways before, most notably at West Whirlaw, but in my view this is one of the most dramatic (and least chronicled) sections of packhorse track in the district. As its name suggests, salt was carried along this route from the salt pans (or 'Wiches') of Cheshire; yet all manner of goods and chattels, not to mention people, must have passed this way down through the centuries (until the Industrial Revolution that is!). Today, there is just the occasional rambler and the moorland wind and rain. What is most striking about this ancient moorland route is its sheer narrowness. If one packhorse train were to meet another coming from the opposite direction there is no way they would have been able to pass each other without one train or the other having to give way and take to the moor. No doubt the issue as to who should 'Give Way' created many a heated argument long ago, when these lonely moorland tracks were busy arteries of communication.

The old causey ascends the hillside to Rake End, where it meanders round the moor edge at the point where the Walsden Valley gives way to Calderdale. A faint path soon appears on the right, heading up the open moor towards the Basin Stone and Gaddings Reservoir. Here is the end of Section 3. For those wishing to get off the Fielden Trail at this point, simply follow the old packhorse way onwards to the Shepherd's Rest Inn on the Lumbutts Road. From here, turn left along the road, then after about a quarter of a mile, turn right down the farm road which eventually leads to Fielden Square in Todmorden (following the Calderdale Way), passing Shoebroad and picking up the latter part of Section 4 en route.

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

By the early 17th century the Inchfield Fieldens were starting to proliferate and prosper. Abraham's brothers were firmly established at Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield. Now, stemming from this new marriage, succeeding generations of Fieldens were to become associated with Bottomley, which is the next stopping point on our journey. Abraham was not the last Fielden to be associated with Inchfield. On the authority of the farmer's wife at Inchfield Fold I am informed that the three storeyed house at Nicklety belonged to one Thomas Fielden; and that the nearby mill, Inchfield Foundry, belonged to one Josiah Fielden, whose sister lived nearby at Inchfield House. Inchfield Fold Farm bears a datestone with the initials GTM 1631 and these, I am told, are the initials of George Travis, who built the house. What of the Fieldens? Well, according to 'Honest John's' family tree there are no 'Fieldens of Inchfield' mentioned after the early 17th century, so perhaps the land was sold off to George Travis, who built the present house.

From Inchfield Fold we simply follow the road into Walsden, emerging onto the busy A6033 road near the local branch library on the left. Cross the road to the Post Office opposite. Here is a chance to purchase refreshments if required.

Walsden is one of those place names with Celtic associations. Like Walshaw near Hebden Bridge it contains the place name element 'Walsh' or 'Welsh', the English term for 'foreigner', implying that there was a 'British' (ie Celtic) enclave in this area for many centuries after the English (and probably also Norman) conquests. Only the English could come along and call the native British 'foreigners' in their own country!

From Walsden Post Office continue onwards towards the church, and on reaching the canal bridge turn right onto the towpath, passing Travis Mill Lock on the left. From here onwards, until we reach Bottomley Bridge we simply follow the canal towpath again.

The Rochdale Canal on this section of the walk is now newly restored. It is a haunt for anglers and waterfowl, and the views to crags and steep hillsides are fascinating. The Rochdale Canal is soon joined by the railway on the right, which, just beyond Bottomley Bridge enters the Summit Tunnel, the first airshaft of which can be seen up on the hillside.

Before we set off for Bottomley let me give you some bits of information about this magnificent railway tunnel, which, when it was constructed, was regarded as being the wonder of its age. Work began on its construction in the spring of 1838, and on 5th September 1839 it claimed the lives of three men and two boys. On 22nd January 1840 three more workers were killed in the tunnel. By 31st March of that year the cost of the tunnel had exeeded the original estimate by 47,051 pounds. Finally, on 11th December 1840 the last brick was keyed in with a silver trowel. According to an account in the Manchester Guardian: "Gentlemen of the first respectability accompanied by numbers of ladies were seen with lighted candles advancing toward the place to witness the ceremony of the completion of the great work. The ladies and gentlemen present were invited to a cold collation at the Summit Inn, while the workmen were regaled within the tunnel". At the time of its completion the Summit Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel in the world, 2885 yards long and containing 23 million bricks.

At Bottomley Bridge we turn left, passing bungalows to ascend a superbly paved packhorse track which snakes up the hillside to Bottomley.

Bottomley

Bottomley is a key place in our Fielden saga. Generations of Quaker (and earlier) Fieldens lived and worked here, and at one time this small cluster of buildings was a small weaving settlement of some note, being situated on the Salter Rake Gate, the main packhorse route over to Lumbutts and Mankinholes, which was an eastern branch of the better known Reddyshore Scout Gate. (The word 'gate' in this context means 'way', and is an old Scandinavian word.) Cotton was spun in later times at nearby Waterstalls Mill. At Bottomley in 1561 lived James Fielden, son of another (unknown) Fielden who lived here in the reign of Edward VI. This James Fielden was great grandfather to the Elizabeth Fielden who married Abraham Fielden of Inchfield. The line runs as follows:

James Fielden Cisley

Jeffrie Fielden (lived at Bottomley in 1567)

James Fielden

Isabel (d. 1594)

Mary J. Clegg

Elizabeth (b 1594)

Abraham Fielden of Inchfield

Abraham and Elizabeth's sons, John and Joshua, as we have already mentioned became Quakers, and from them all the 'Bottomley Fieldens' are descended.

When I arrived at Bottomley whilst surveying the Fielden Trail, the weather was stifingly hot and the farmer there, Mr. Stansfield, invited us (the dog and I) in for a drink. Mr. Stansfield told me that as a boy he had farmed up at Kebs and Bridestones (this is, of course Stansfield ancestral territory). I thought it strange that just as Nicholas Fielden had inherited Stansfield lands by marriage way back in the 16th century, now, in the 20th century a Stansfield was in possession of lands that had traditionally belonged to the Fieldens since time immemorial! Strange indeed are the workings of fate.

Before we continue on our way, here is a little anecdote concerning the Fieldens of Bottomley:

"When Jane Fielden was a girl of nine years old, her grandfather, Samuel Fielden of Bottomley gave her a soup plate, which bears on the flat part a florid picture of Katharine of Aragon, stating that it belonged to her great grandmother and grandmother, who was then dead. 'It had always belonged to a Jane . . .' She kept it carefully until as an old widow woman living with her daughter at Strines Barn Walsden, she gave it to her grand daughter Jane Crowther, afterwards

Bottomley, home of the Quaker Fieldens.

wife of John Travis, who gave it, (again) to her niece Jane (Crossley) Stenhouse, a few years before her death; so that the piece of old delfware is still travelling with the name 'Jane' .. .

From Bottomley the route crosses Bottomley Clough to emerge behind Deanroyd Farm. Then an old packhorse route, paved in parts, contours along the hillside to Hollingworth Gate, where we enter a metalled road leading to North Hollingworth.

Hollingworth too, has Fielden associations: Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden's son, Joshua (1) of Bottomley ('Honest John's' great great grandfather) married Martha Greenwood of Hollingworth before a J.P. on 21st October 1656. Their third son, Thomas, inherited Hollingworth, and he lived there until his death in 1762. There are three farmsteads here: Hollingworth Gate, South Hollingworth and North Hollingworth. As to which of these three houses was the residence of Thomas Fielden, is a question I am unable to answer. I would hazard a guess at South Hollingworth, but really the 'Fieldens of Hollingworth' demand more intensive research.

From Hollingworth Gate the tarmac road continues to North Hollingworth. Here, turn right, then left to a walled lane leading to a gate at the edge of open moorland. Beyond the gate is an extremely well preserved packhorse causey, which leads over moorland to Rake End. This is the Salter Rake Gate, an ancient route dating back to times unrecorded.

For my money this is one of the most interesting parts of the Fielden Trail. True, we have encountered old packhorse ways before, most notably at West Whirlaw, but in my view this is one of the most dramatic (and least chronicled) sections of packhorse track in the district. As its name suggests, salt was carried along this route from the salt pans (or 'Wiches') of Cheshire; yet all manner of goods and chattels, not to mention people, must have passed this way down through the centuries (until the Industrial Revolution that is!). Today, there is just the occasional rambler and the moorland wind and rain. What is most striking about this ancient moorland route is its sheer narrowness. If one packhorse train were to meet another coming from the opposite direction there is no way they would have been able to pass each other without one train or the other having to give way and take to the moor. No doubt the issue as to who should 'Give Way' created many a heated argument long ago, when these lonely moorland tracks were busy arteries of communication.

The old causey ascends the hillside to Rake End, where it meanders round the moor edge at the point where the Walsden Valley gives way to Calderdale. A faint path soon appears on the right, heading up the open moor towards the Basin Stone and Gaddings Reservoir. Here is the end of Section 3. For those wishing to get off the Fielden Trail at this point, simply follow the old packhorse way onwards to the Shepherd's Rest Inn on the Lumbutts Road. From here, turn left along the road, then after about a quarter of a mile, turn right down the farm road which eventually leads to Fielden Square in Todmorden (following the Calderdale Way), passing Shoebroad and picking up the latter part of Section 4 en route.

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

wife of John Travis, who gave it, (again) to her niece Jane (Crossley) Stenhouse, a few years before her death; so that the piece of old delfware is still travelling with the name 'Jane' .. .

From Bottomley the route crosses Bottomley Clough to emerge behind Deanroyd Farm. Then an old packhorse route, paved in parts, contours along the hillside to Hollingworth Gate, where we enter a metalled road leading to North Hollingworth.

Hollingworth too, has Fielden associations: Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden's son, Joshua (1) of Bottomley ('Honest John's' great great grandfather) married Martha Greenwood of Hollingworth before a J.P. on 21st October 1656. Their third son, Thomas, inherited Hollingworth, and he lived there until his death in 1762. There are three farmsteads here: Hollingworth Gate, South Hollingworth and North Hollingworth. As to which of these three houses was the residence of Thomas Fielden, is a question I am unable to answer. I would hazard a guess at South Hollingworth, but really the 'Fieldens of Hollingworth' demand more intensive research.